Enzymes are a subset of receptor-like proteins that are

directly responsible for catalyzing the biochemical reactions that sustain

life. For example, digestive enzymes act to break down the nutrients of

our diet. DNA polymerase and related enzymes are crucial for cell division

and replication. Enzymes are genetically programmed to be absolutely

specific for their appropriate molecular targets. Any errors could have

grave consequences. One can imagine the end result should blood clotting

enzymes start activating throughout the body. Or consider the problems

that arise when our immune system attacks our own tissues. Enzymes ensure

the specificity of their targets by forming a molecular environment that

excludes interactions with inappropriate molecules. The analogy most often

mentioned is that of a lock and key. The enzyme is a molecular lock, which

contains a keyhole that exhibits a very specific and consistent size and

shape. This molecular keyhole is termed the active site of the

enzyme and allows interaction with only the appropriate molecular targets.

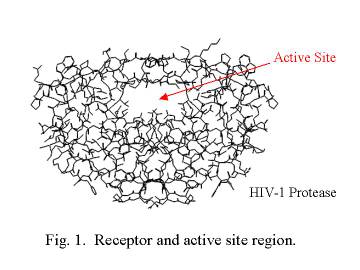

Just as a typical lock is much bigger than the keyhole, the receptor is usually

much larger than the active site. The receptor, as specified by our DNA,

is a folded protein whose major purpose is to form and maintain the size and

shape of the active site. This is illustrated in Figure 1 using the

structure of the HIV-1 protease.

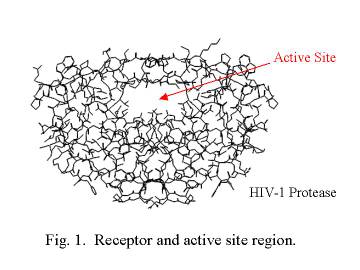

The most important concept in drug design is to understand the methods by which the active site of a receptor selectively restricts the binding of inappropriate structures. Any potential molecule that can bind to a receptor is called a ligand. In order for a ligand to bind, it must contain a specific combination of atoms that presents the correct size, shape, and charge composition in order to bind and interact with the receptor. In essence, the ligand must possess the molecular key that binds the receptor lock. Figure 2 schematically shows a typical ligand-receptor binding interaction.

Figure 2. Enzyme substrate complementary interactions.

We see here that a putative ligand-receptor interaction must have complementary size and shape. This is termed steric complementarity. As is the case with an actual key, if a different molecule varies by even a single atom in the wrong place, it may not fit properly, and will most likely not interact with the receptor. However, the more closely the fit between the ligand and receptor, the more tightly the interaction becomes. Again, keep in mind that this is only a two-dimensional schematic. Both ligand and active site are volumes with complex three-dimensional shape.

In addition to steric complementarity, electrostatic interactions influence ligand binding. Charged receptor atoms often surround the active site, imparting a localized charge is specific regions of the active site. From physics, we know that opposite charges attract while similar charges repel. Electrostatic complementarity further restricts the binding of inappropriate molecules since the ligand must contain correctly placed complementary charged atoms for interaction to occur.

The main driving force for ligand and receptor binding is hydrophobic interaction. Nearly two-thirds of the body is water, and this aqueous milieu surrounds all our cells. In order for ligand and receptor to interact, there must be a driving force that compels the ligand to leave the water and bind to the receptor. The hydrophobicity of a ligand is what causes this. Hydrophobicity stands for 'water fearing' and is a measure of how 'greasy' a compound is. It can be roughly approximated by the percentage of hydrogen and carbon in the molecule. This force is easily demonstrated by placing a few drops of oil in a cup of water. The oil is composed of hydrocarbon chains and is highly hydrophobic. The oil droplets will instantly coalesce into a single globule in order to avoid the water, which is highly polar. As shown in Figure 2, the active site may contain a mixture of hydrophobic pockets and regions that are more polar. Since the hydrophobic portions of the ligand and receptor prefer to be juxtaposed, the arrangement of hydrophobic surfaces provides yet another way that receptors can limit the binding of inappropriate targets.

As discussed above, there are numerous potential interactions between ligand and receptor. Depending upon the size of the active site, there may be a myriad steric, electrostatic, and hydrophobic contacts. However, some are more important than others. The specific interactions that are crucial for ligand recognition and binding by the receptor are termed the pharmacophore. Usually, these are the interactions that directly factor into the structural integrity of a receptor or are involved in the mechanism of its action. Using our lock and key analogy from above, we can imagine a lock having numerous tumblers. There may be many keys that can sterically complement the lock and fit within the keyhole. However, all but the correct key will displace the wrong tumblers, leading to a sub-optimal interaction with the lock. Only the correct key, which presents the pharmacophore to the receptor, contacts the appropriate tumblers and properly interacts with the lock to open it. This is crucial to the design of pharmaceuticals since any successful drug must incorporate the appropriate chemical structures and present the pharmacophore to the receptor.

This is shown in Figure 3 above. In the upper left frame of this figure, we see our native ligand bound within the active site. Assume that through biochemical investigation, we determine that the phenyl ring (blue) and the carboxylic acid group (green) are vital to receptor interaction. Thus, we deduce that these two groups must be the pharmacophore that a ligand must present to the receptor for binding. In future drugs that we develop to mimic the native ligand, we must include these two pharmacophoric elements for successful binding to occur. This is shown in the upper right derivative compound where a bicyclic group has been substituted. Because it maintains the pharmacophore and retains its complementary size and shape, it has a reasonable chance of successfully binding. However, any drug that we develop which lacks a complete pharmacophore may not interact with the receptor target.

Prev - What are Drugs?

Next - The Challenge of Drug Design

Return to RACHEL Technology - Main

(c) 2002 Drug Design Methodologies, LLC. All Rights Reserved